- *Corresponding Author:

- R. A. Z. Michael

Centre for Biotechnology, Department of Chemical Engineering, AUCE, Andhra University, Andhra Pradesh- 530003, India

E-mail: michaelzerubabel@hotmail.com

| Date of Received | 10 July 2020 |

| Date of Revision | 23 Ocotober 2020 |

| Date of Acceptance | 25 January 2021 |

| Indian J Pharm Sci 2021;83(1):39-44 |

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms

Abstract

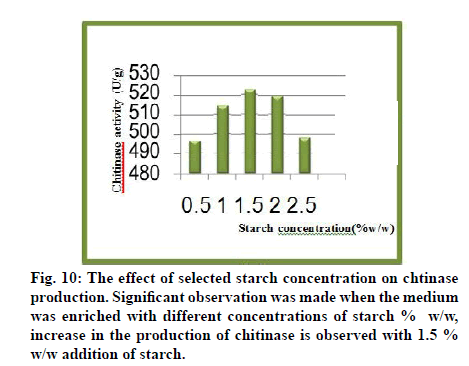

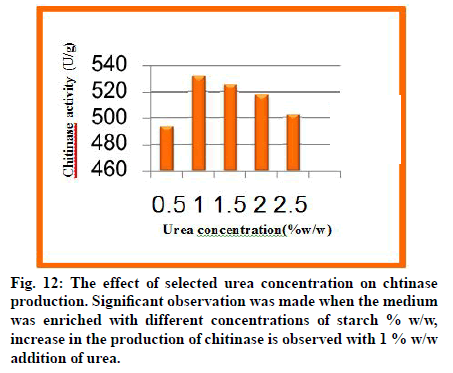

Chitinases have huge potential applications and biological value in industries, they are used in generating single cell proteins, sweeteners, insecticides, antifungal drugs, anti-cancer agents, biopesticides, food processing agents, degrading agents for sea waste etc. Chitinases are used for the conversion of chitin a polysaccharide into monomers. Chitin is produced enormously in the biosphere annually from fungal cell walls, exoskeletons of insects and crustaceans. Chitinases producing microorganisms Bacillus licheniformis, Chromobacterium violaceum, Rhizobium radiobacter, Streptomyces griseous were obtained from microbial type culture collection. Solid state fermentation was done on Naturally available substrates like Fish scale waste, Prawn shell waste, Wheat bran, Potato peel, Grape leaf to check the enhanced production of Chitinase. Prawn shell waste was found to be the best natural substrate for high activity of Chitinase (464.98 U/g). The overall maximum yield of Chitinase, Chtinolytic activity (531.66 U/gds) was achieved with the optimized process parameters of incubation time(60th h), temperature(34°), inoculum age(3rd d), inoculums volume(20 % v/w), pH(7.0) moisture content 60 % v/w), 1.5 % w/w starch as Carbon source supplement and 1 % w/w urea as Nitrogen source supplement. Both physico-chemical and nutritional parameters had played a significant role in the production of the Chitinase enzyme.

Keywords

Chitinase, chitin, chromobacterium violaceum, chitinolytic activity, solid state fermentation

Chitin is the insoluble polysaccharide which consists of β-1, 4-linked to N-acetyl-β-glucosamine. Chitin was broken down to its monomer NAG by chitinases, which this process called chitinolysis. Chitin has high resistance to organic solvent and requires strong mineral acids for solubilization. Chitin and its derivatives are biodegradable and biocompatible to human and most of the animal[1].

Chitinase is monomeric protein that forms in single strand of polypeptide with molecular weight range in between 21 kDa to 70 kDa. Chitinase also known as poly 1,4-(N-acetyl-β- D-glucosaminide) glycanohydrolase, (EC 3.2.2.14). Chitinase have been classified into families 18 and 19 of the glycosyl hydrolase superfamily, and chitobiases, to family 20. These families are grouping based on primary structure comparisons and it is well established that enzymes that belong to the same family share several common properties in terms of folding of the catalytic domain, substrate specificity, and stereochemistry of the reaction as well as catalytic mechanism. Chitinase is capable to cleave the bond between C1 and C4 of two consecutive N-acetyl-glucosamines of a chitin polymer into low molecular weight product[2]. Broadly, chitinase are classified as the endochitinases, 2 N- acetylglucosaminide and exochitinases. The exochitinases are defined as the progressive action starting from the nonreducing end of the chitin with release of successive diacetyl chitobiose units. N-acetyl-glucosaminide plays a role in the activities are defined as a random cleavage at the internal point in the chitin chain[1]. Chitinases was produced by wide range of microorganisms such as fungi, bacteria, actinomycetes, streptomyces, crustaceans, and insect as well as organisms that do not contain chitin such as viruses, higher plants, animals and humans[3]. Recently, chitinases have been receiving attention because of their possible application for biological control of chitin-containing organisms and also for the exploitation of natural chitinous materials[4]. Chitinases are used extensively in biological control for the protoplasts due to its ability to degrade fungal cell wall and it makes an attractive alternative as an environmentally safe bio control agent. Furthermore, the ability of chitinase to hydrolyze chitin makes it very useful for production of value added products such as sweeteners, growth factors and single cell protein[1]. Purification and characterization of chitinase producing bacteria is important due to the microbial chitinase’s application in agricultural and pollution control. Purification process is mean by separation of interest protein from mixture of protein while maintain its biological function. This can be conduct by controlling the pH, temperature, and ionic strength of the interest enzyme. All purification method is designed based on molecular size, electrostatic properties, and relative solubility in salts until purification homogeneity achieved.

Materials and Methods

Microorganism used and inoculum preparation:

Chitinase producing Bacillus licheniformes (Microbial Type Culture Collection (MTCC) 429), Chromobacterium violaceum (MTCC 2656), Rhizobium radiobates (MTCC 8917), Streptomyces gresius (MTCC 4734) obtained from MTCC, Chandigarh, were used in the present study. The strains were grown and maintained on yeast manitol, Nutrient agar and streptomyces medium, respectively. After cultivating for 2-3 d at 30°, cultures were preserved at 4° for short term storage and were sub cultured every 4 w. The production of chitinase enzyme requires the preparation of inoculum. Culture was scraped and washed from the slant culture with 10 ml sterile water and 2 ml of the inoculum was added to each 250 ml flasks containing production medium.

Chemicals used:

For Colloidal chitin: Concentrated HCl and Chitin, For Acetate Buffer; Acetic acid and sodium acetate, For citrate phosphate buffer; citrate phosphate and citric acid, For DNS Reagent; 3,5-dinitrosalicyclic acid, Sodium potassium tartarate and Sodium hydroxide

Preparation of Colloidal Chitin:

10.0 g Colloidal chitin was prepared according to the modified method of Shimahara and Takiguchi[5] 10 g of chitin flakes from crab shells (Sigma-Aldrich, C9213) were mixed with 200 ml concentrated HCl on ice with vigorous stirring for 3-4 h and continued incubation on ice overnight. Then, the mixture was filtered through cheesecloth and dropped slowly into 600 ml of 50 % ice-cold ethanol with rapid stirring on ice. Then, the colloidal chitin was collected by centrifugation at 8000 rpm, for 30 min at 4° and washed several times with tap water until the pH was neutral (pH 7.0). Alternatively the filtrate was re-filtered with suction through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and washed with water until the washing solution was neutral. The colloidal chitin was kept at 4° untilused[6].

Substrate used in solid state fermentation:

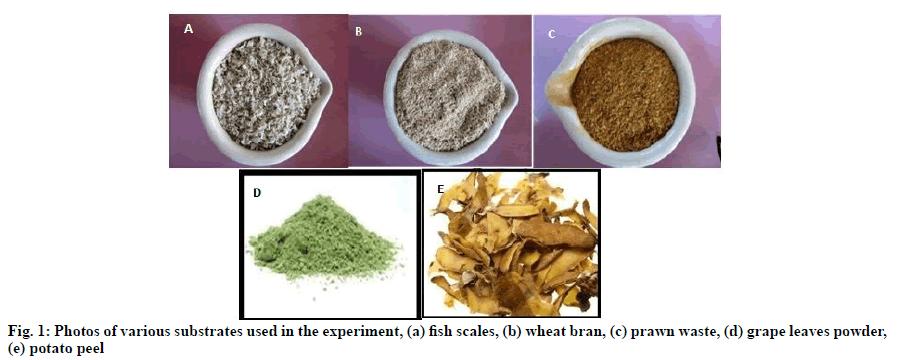

In the present study, five substrates which are Wheat Brawn, Prawn shell Waste, Fish Scale, potato peel and grape leaf were used in the production of Chitinase. Fish scale waste, prawn waste, wheat bran was collected at local fish market (MVP colony, Visakhapatnam) and dried and grinded with mixer (fig. 1). 5 g of individual powder taken in 250 ml Erlenmeyer flask and mixed with distilled water to a solid liquid ratio of 5:4 (w/v). The thoroughly mixed substrate was autoclaved for 20 min at 121°, 15 lb and cooled to room temperature. Under aseptic conditions, the sterilized solid state medium was inoculated with 2 ml (23×106 c.f.u/ml.) spore inoculum. The contents were mixed thoroughly and the flaks were placed in an incubator at 34° for 60 h intervals[7].

Enzyme extraction:

After incubation, the fermented solid was mixed with 25 ml (5×volume, based on initial dry weight of the substrate) distilled water and mixed thoroughly on a rotary shaker 150 rpm for 30 min. The entire contents were squeezed through a whatmann no 1 filter paper. After extracting twice the extracts were pooled, centrifuged at 4° for 20 min at 10,000 rpm and the clear supernatant was used as crude enzyme for assay[8].

Analytical procedures:

Chitinase activity was measured by incubating 1 ml of enzyme solution with 1 % 0.3 ml of colloidal chitin with addition of 0.3 ml 1 % acetate buffer (pH 7.0) at 37° for 1 h. The catalytic reaction was terminated and analyzed on adding dinitrosalicylic acid reagent (0.5 ml). The mixture was boiled for 15 min, chilled and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min to remove insoluble chitin. The resulting adduct of reducing sugars were measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm[7].

Results and Discussion

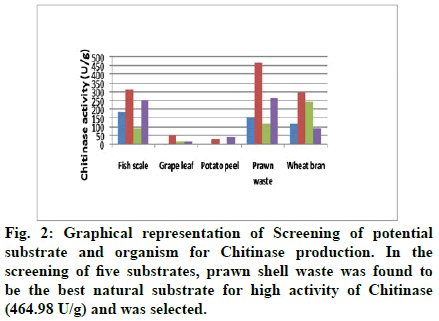

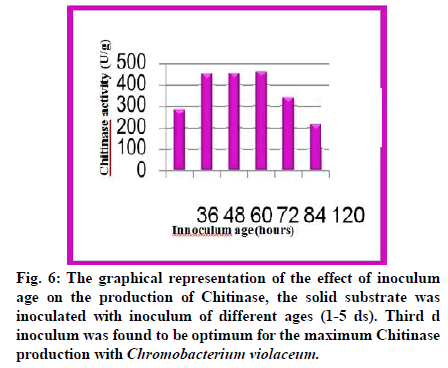

In Solid State Fermentation (SSF), the selection of a suitable solid substrate for a fermentation process is a critical factor and thus involves the screening of a number of agro-industrial materials for microbial growth and product formation. In the present study, five substrates, viz. Wheat Bran, Prawn Waste, Fish Scale, potato peel, grape leaf were screened for growth and production of Chitinase using various strains viz Bacillus licheniformes (MTCC 429), Chromobacterium violaceum (MTCC 2656), Rhizobium radiobates (MTCC 8917), Streptomyces gresius (MTCC 4734). All the substrates and strains supported growth and production of Chitinase, while fish scales and prawn waste was proved superior to other substrates and Chitinase activity of 315.28 U/g and 464 U/g were obtained using Chromobacterium violaceum (MTCC 2656). SSF process was observed to be less sensitive to contamination than submerged fermentation[9]. Solid substrate fermentation holds tremendous potential for the production of microbial enzymes[10](fig. 2-5). Solid substrate fermentation can be of special interest in those processes in which the crude fermented product may be used directly as an enzyme source[11]. Different types of substrates which contain chitin have been tried for the production of chitinase which included fungal cell wall, crab and shrimp shells, wheat bran, prawn waste[8,12-16]. As prawn waste supported maximum enzyme activity with Chromobacterium violaceum this combination was chosen for in depth study (fig. 6-8).

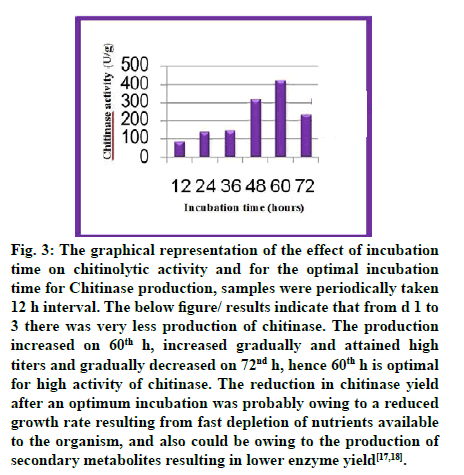

Fig. 3: The graphical representation of the effect of incubation time on chitinolytic activity and for the optimal incubation time for Chitinase production, samples were periodically taken 12 h interval. The below figure/ results indicate that from d 1 to 3 there was very less production of chitinase. The production increased on 60th h, increased gradually and attained high titers and gradually decreased on 72nd h, hence 60th h is optimal for high activity of chitinase. The reduction in chitinase yield after an optimum incubation was probably owing to a reduced growth rate resulting from fast depletion of nutrients available to the organism, and also could be owing to the production of secondary metabolites resulting in lower enzyme yield[17,18].

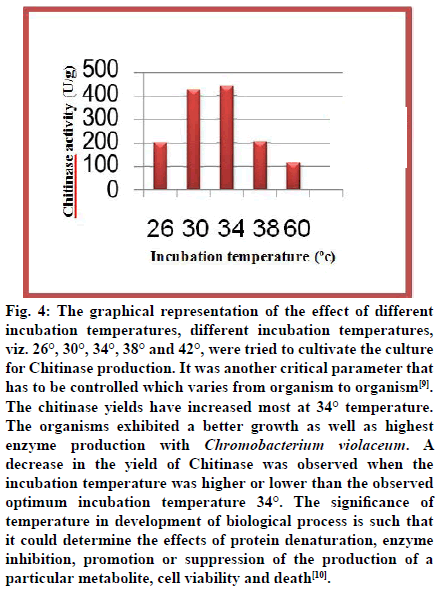

Fig. 4: The graphical representation of the effect of different incubation temperatures, different incubation temperatures, viz. 26°, 30°, 34°, 38° and 42°, were tried to cultivate the culture for Chitinase production. It was another critical parameter that has to be controlled which varies from organism to organism[9]. The chitinase yields have increased most at 34° temperature. The organisms exhibited a better growth as well as highest enzyme production with Chromobacterium violaceum. A decrease in the yield of Chitinase was observed when the incubation temperature was higher or lower than the observed optimum incubation temperature 34°. The ignificance of temperature in development of biological process is such that it could determine the effects of protein denaturation, enzyme inhibition, promotion or suppression of the production of a particular metabolite, cell viability and death[10].

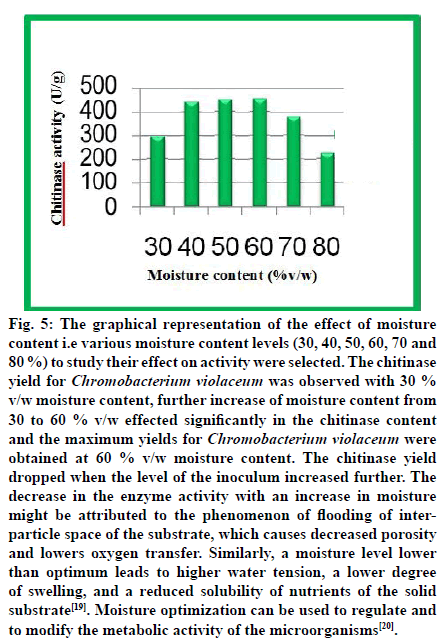

Fig. 5: The graphical representation of the effect of moisture content i.e various moisture content levels (30, 40, 50, 60, 70 and 80 %) to study their effect on activity were selected. The chitinase yield for Chromobacterium violaceum was observed with 30 % v/w moisture content, further increase of moisture content from 30 to 60 % v/w effected significantly in the chitinase content and the maximum yields for Chromobacterium violaceum were obtained at 60 % v/w moisture content. The chitinase yield dropped when the level of the inoculum increased further. The decrease in the enzyme activity with an increase in moisture might be attributed to the phenomenon of flooding of interparticle space of the substrate, which causes decreased porosity and lowers oxygen transfer. Similarly, a moisture level lower than optimum leads to higher water tension, a lower degree of swelling, and a reduced solubility of nutrients of the solid substrate[19]. Moisture optimization can be used to regulate and to modify the metabolic activity of the microorganisms[20].

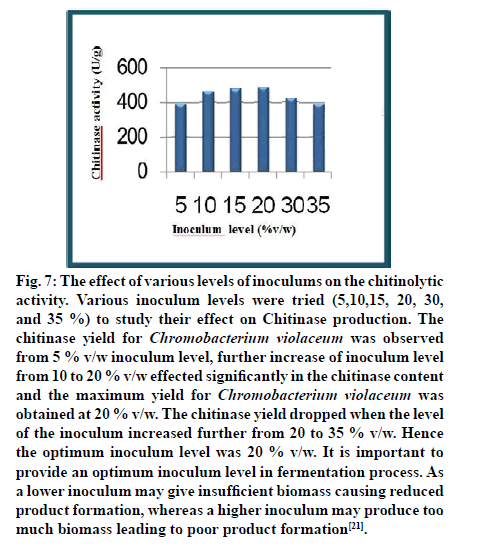

Fig. 7: The effect of various levels of inoculums on the chitinolytic activity. Various inoculum levels were tried (5,10,15, 20, 30, and 35 %) to study their effect on Chitinase production. The chitinase yield for Chromobacterium violaceum was observed from 5 % v/w inoculum level, further increase of inoculum level from 10 to 20 % v/w effected significantly in the chitinase content and the maximum yield for Chromobacterium violaceum was obtained at 20 % v/w. The chitinase yield dropped when the level of the inoculum increased further from 20 to 35 % v/w. Hence the optimum inoculum level was 20 % v/w. It is important to provide an optimum inoculum level in fermentation process. As a lower inoculum may give insufficient biomass causing reduced product formation, whereas a higher inoculum may produce too much biomass leading to poor product formation[21].

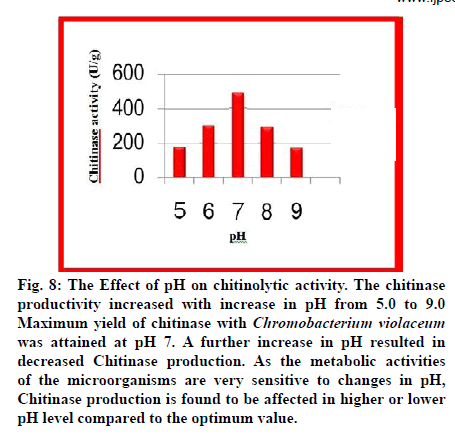

Fig. 8: The Effect of pH on chitinolytic activity. The chitinase productivity increased with increase in pH from 5.0 to 9.0 Maximum yield of chitinase with Chromobacterium violaceum was attained at pH 7. A further increase in pH resulted in decreased Chitinase production. As the metabolic activities of the microorganisms are very sensitive to changes in pH, Chitinase production is found to be affected in higher or lower pH level compared to the optimum value.

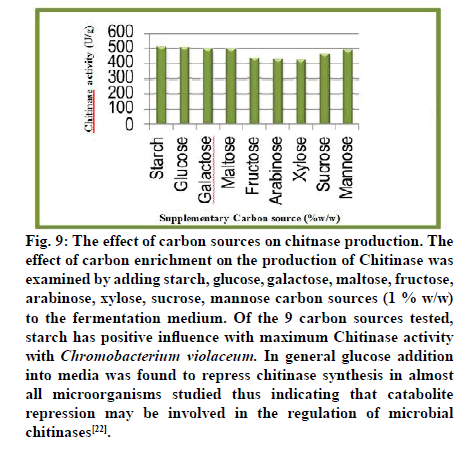

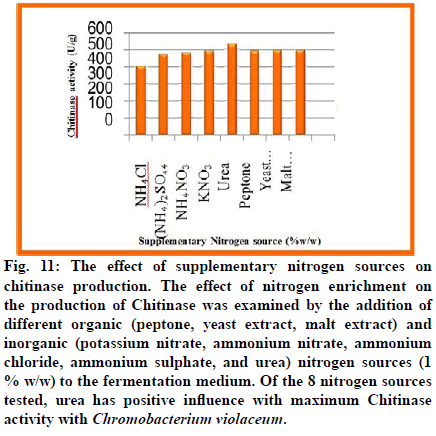

The physicochemical parameters like incubation time, temperature, inoculum age, inoculum volume, pH and moisture content were optimized. The nutritional supplementation study was carried out using various nitrogen sources to enrich the production medium to enhance the enzyme yield. The results of study presented and discussed in the light of existing literature (fig. 9-12).

Fig. 9: The effect of carbon sources on chitnase production. The

effect of carbon enrichment on the production of Chitinase was

examined by adding starch, glucose, galactose, maltose, fructose,

arabinose, xylose, sucrose, mannose carbon sources (1 % w/w)

to the fermentation medium. Of the 9 carbon sources tested,

starch has positive influence with maximum Chitinase activity

with Chromobacterium violaceum. In general glucose addition

into media was found to repress chitinase synthesis in almost

all microorganisms studied thus indicating that catabolite

repression may be involved in the regulation of microbial

chitinases[22].

Fig. 11: The effect of supplementary nitrogen sources on chitinase production. The effect of nitrogen enrichment on the production of Chitinase was examined by the addition of different organic (peptone, yeast extract, malt extract) and inorganic (potassium nitrate, ammonium nitrate, ammonium chloride, ammonium sulphate, and urea) nitrogen sources (1 % w/w) to the fermentation medium. Of the 8 nitrogen sources tested, urea has positive influence with maximum Chitinase activity with Chromobacterium violaceum.

In this study, the optimal conditions for chitinase production from Chromobacterium violaceum MTCC 2656 were determined using SSF method. A partial characterization was also performed, where the optimum temperature, moisture content, inoculum age and volume, pH, carbon and nitrogen sources were determined to obtain the best chitinase activity. The present study suggests that solid waste from prawn waste can be used as suitable substrate for chitinase production using Chromobacterium violaceum. Maximum chitinase activity of 531.66 U/g with Chromobacterium violaceum MTCC 2656, it can be comparable with earlier reports. Exploitation of prawn waste, not only solve the severe problem in disposal of solid waste but also used for value added important chitinase which has immense commercial value and is economical.

References

- Felse PA, Panda T. Production of microbial chitinases-A revisit. Bioproc Eng 2000;23(2):127-34.

- Gokul B, Lee JH, Song KB, Rhee SK, Kim CH, Panda T. Characterization and applications of chitinases from Trichoderma harzianum-a review. Bioproc Eng 2000;23(6):691-4.

- Ratledge C, editor. Physiology of biodegradative microorganisms. Springer Science & Business Media 2012;177-190.

- Ohno T, Armand S, Hata T, Nikaidou N, Henrissat B, Mitsutomi M, et al. A modular family 19 chitinase found in the prokaryotic organism Streptomyces griseus HUT 6037. J Bacteriol 1996;178(17):5065-70.

- Shimahara K, Takiguchi Y. Preparation of crustacean chitin. Method Enzymol 1988;161:417-23.

- Songsiriritthigul C, Lapboonrueng S, Pechsrichuang P, Pesatcha P, Yamabhai M. Expression and characterization of Bacillus licheniformis chitinase (ChiA), suitable for bioconversion of chitin waste. Bioresource Technol 2010;101(11):4096-103.

- Wu YJ, Cheng CY, Li YK. Cloning and Expression of Chitinase A from Serratia marcescens for Large-Scale Preparation of N, N-Diacetyl Chitobiose. J Chin Chem Soc 2009;56(4):688-95.

- Suresh PV, Chandrasekaran M. Utilization of prawn waste for chitinase production by the marine fungus Beauveria bassiana by solid state fermentation. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 1998;14(5):655-60.

- Sandhya C, Adapa LK, Nampoothiri KM, Binod P, Szakacs G, Pandey A. Extracellular chitinase production by Trichoderma harzianum in submerged fermentation. J Basic Microbiol 2004;44(1):49-58.

- Pandey A, Soccol CR, Rodriguez-Leon JA, Nigam PS. Solid State Fermentation in Biotechnology: Fundamentals and Applications Reference Book 2001;100-221

- Tengerdy RP, Szakacs G. Solid state enzymes for agrobiotechnology. Agro Food Industry Hi-Tech 2000;11(5):36-8.

- Tagawa K, Okazaki K. Isolation and some cultural conditions of Streptomyces species which produce enzymes lysing Aspergillus niger cell wall. J Ferment Bioeng 1991;71(4):230-6.

- Wang SL, Chang WT. Purification and characterization of two bifunctional chitinases/lysozymes extracellularly produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa K-187 in a shrimp and crab shell powder medium. Applied Environment Microbiol 1997;63(2):380-6.

- Cosio IG, Fisher RA, Carroad PA. Bioconversion of shellfish chitin waste: waste pretreatment, enzyme production, process design, and economic analysis. J Food Sci 1982;47(3):901-5.

- Nampoothiri KM, Baiju TV, Sandhya C, Sabu A, Szakacs G, Pandey A. Process optimization for antifungal chitinase production by Trichoderma harzianum. Process Biochem 2004;39(11):1583-90.

- Chernin LS, Winson MK, Thompson JM, Haran S, Bycroft BW, Chet I, et al. Chitinolytic activity in Chromobacterium violaceum: substrate analysis and regulation by quorum sensing. J Bacteriol 1998;180(17):4435-41.

- Nampoothiri KM, Baiju TV, Sandhya C, Sabu A, Szakacs G, Pandey A. Process optimization for antifungal chitinase production by Trichoderma harzianum. Process Biochem 2004;39(11):1583-90.

- Sandhya C and Ashok P. Role of Glucoamylases in Biotechnology. In: Microbial diversity: Current perspectives and potential applications by Satyanarayana and Johri BN. IK International House Pvt Ltd pp 679-694.

- Pandey A, Ashakumary L, Selvakumar P, Vijayalakshmi KS. Influence of water activity on growth and activity of Aspergillus niger for glycoamylase production in solid-state fermentation. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 1994;10(4):485-6.

- Matsumoto Y, Saucedo-Castañeda G, Revah S, Shirai K. Production of ß-N-acetylhexosaminidase of Verticillium lecanii by solid state and submerged fermentations utilizing shrimp waste silage as substrate and inducer. Process Biochem 2004;39(6):665-71.

- Mudgetti RE. Manual of industrial biotechnology. Am Soc Microbiol 1986;21:285-95.

- Saito A, Fujii T, Yoneyama T, Miyashita K. glkA is involved in glucose repression of chitinase production in Streptomyces lividans. J Bacteriol 1998;180(11):2911-4.