- *Corresponding Author:

- W. Phimarn

Social Pharmacy Research Unit, Faculty of Pharmacy, Mahasarakham University, Kantharawichai, Maha Sarakham-44150, Thailand

E-mail: wiraphol.p@msu.ac.th

| Date of Submission | 23 June 2016 |

| Date of Revision | 30 October 2016 |

| Date of Acceptance | 31 December 2016 |

| Indian J Pharm Sci 2017;79(1): 35-41 |

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms

Abstract

This study was carried out to compare groups with individual counseling to examine essential outcomes in young adults in a community pharmacy. A randomized controlled trial was conducted from June 2011 to February 2012. A total of 112 overweight and obese participants were randomly assigned to receive group counseling (n=52) or individual counseling (n=56). Clinical outcomes included weight, waist circumference and body mass index. Eating behaviors were evaluated by a theory of planned behavior questionnaire. Both groups showed significant clinical outcomes. The theory of planned behavior average sum score significantly increased from baseline in the health dieting behavior and subjective norm in group counseling. In the individual group (P<0.05), the score increased significantly from baseline only for health dieting behavior (P<0.05). The logistic regression analysis, factors associated with eating behaviors were: group counseling (OR=4.03, 95% CI: 1.71-9.51), female (healthy dieting behavior: OR=0.37, 95% CI: normative beliefs: 0.15-0.93) and person who attempted to control weight (OR=0.17, 95% CI: 0.03-0.91). Group counseling was not inferior to individual counseling and the group counseling should be used as first line mode for weight control management in young adults.

Keywords

Obesity, young adults, community pharmacy, body mass index, theory of planned behaviour

Overweight and obesity are major risk factors of several chronic diseases. Prevalence of overweight and obesity is increasing in all age groups [1,2]. Recently, the World Health Organisation (WHO) reported that more than one billion adults worldwide are overweight; of these over 200 million men and almost 300 million women were obese. Over 40 million children aged <5 y were overweight in 2011 [3].

In Thailand, the prevalence of obesity in adults (body mass index; BMI≥25 kg/m2) increased to 22.4% in men and 34.3% in women in 2004 [4]. Especially, there is increasing rate among children and adolescents [5]. The national representative data on the status of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents are available for several countries in Asia including Thailand [6].

Lifestyle modification have been reported as the most effective strategy to manage obesity and overweight [7]. Understanding patients with healthy eating behaviour is also recommended in identifying a root cause of overweight. Evidence proved that the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is of use to explain eating behaviour [8-11] since this theory is able to explore intention of eating behaviour [12]. A previous study in Thailand designed the TPB diet questionnaire in Thai and suggested this tool was beneficial for health professionals providing lifestyle advice to people who are overweight and obese [13]. Even counselling option could be responsible for improved clinical outcomes. The previous studies were conflicting [14-16] and most of the studies were performed in adults. Only a few studies have compared group versus individual counselling reducing weight in overweight and obese young adults. The study aimed to examine clinical outcomes, eating behaviour as measured by the TPB diet questionnaire and explore the factors associated with eating behaviour.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The study was a parallel group, open labelled randomized controlled trial at a community pharmacy located on the Mahasarakham University campus. The trial was undertaken from June 2011 to February 2012. Ethical approval was received from Mahasarakham University. Consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants

The target population was overweight and obese young adults at the University community pharmacy in Mahasarakham University, located in Northeast Thailand. Optimal sample size was calculated using the following Eqn., n = 2 [(Zα+Zβ)σ]2/(μc-μt)2. Parameters used for calculation were based on standard practice (Zα=1.645, Zβ=0.840) and previous research, which reported the change in weight due to intervention (α=2.48, μc=0, μt=−1.5) [17]. Moreover, 30% of number of participants for loss of follow up was added. This suggested the appropriate number of participants should be at least 45 in each group. Eligible criteria were university students with body mass index (BMI) at least 25 kg/m2, having an intention to control their weight, willingness to follow the study protocol and having a physically active lifestyle. Exclusion criteria were those using medications or herbal products known to affect weight, participating in any weight control programs. All participants met criteria were invited to participate. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participant personal information was kept confidential. They were randomly assigned to either the group counselling or the individual counselling.

Intervention

Two community pharmacists, who provided weight loss advice routinely, developed the weight loss handbook. All participants were given a goal of achieving a 6% weight loss over a 6 mon period. This was based on a goal of 1% weight loss per month. The participants were instructed to maintain their usual physical activity throughout the study. A nutritionally balanced, low calorie diet consisting of approximately 1200-1500 kcal/d for women and 1500 to 1800 kcal/d for men, with approximately 55% of calories from carbohydrate, 30% from fat, and 15% from protein [18]. Both groups received the necessary information such as rationale of healthy dieting for weight control, principles of energy intake, food groups, portion size, and principle and strategies of behaviour intervention. This information provided by pharmacist providers lasted for about 1 h. Common local foods that provided high calories from carbohydrate such as sticky rice, dessert and Thai sweet fruits such as banana, mango, and jackfruit were emphasized because these foods are a major cause of overweight and obesity in the Thai population. Participants were informed that all components of interventions were similar between the two groups, except for mode of interventions.

A weight control handbook was provided to all participants for self-study. The handbook is comprised of four parts: (1) an informational section which deals with healthy diet, principles of calorie intake, food groups, portion size, and exercise, (2) a patient profile to record personal information and clinical outcomes; weight (kg), height (m), waist circumference (inches), and BMI (kg/m2) (3) a daily food record for patients to record their daily meals and (4) a daily exercise record for themselves. Prior to the study, the handbook was provided to the two pharmacists as a standard guide for their use in counselling.

Group counselling

Participants in the group counselling about weight loss included 8-10 overweight and obese people who were scheduled to visit the community pharmacy on a predetermined day that enabled them to attend the group advisory session together. The group sessions lasted approximately 1 h and covered information about healthy diet, principles of energy intake, food groups, portion size, and exercise. The group counselling sessions were provided at 0, 3 and 6 mon. Outcomes were measured as described below.

Individual counselling

Participants assigned to the individual counselling were scheduled to visit the selected community pharmacy. At 0 mon, the weight loss handbook was provided to all experimental group participants for self-study. Participants received an individual counselling session at every visit (0, 3 and 6 mon) from the same pharmacist. The counselling sessions lasted approximately 1 h and focused on healthy dieting and exercise. Outcomes were measured as described below.

Outcomes and data collections

Clinical outcomes included body weight, waist circumference, height and BMI; assessed at all patient visits (0, 3 and 6 mon) using standard medical devices. Waist circumference was assessed at the narrowest point superior to the hip. Amount of dietary intake was evaluated at baseline and 3 mon using 3 d dietary record. The questionnaire was developed based on the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) for healthy dieting behaviour (the TPB diet questionnaire; Thai version) and was used to assess healthy dieting behaviour, intention to perform healthy dieting behaviour, attitude toward healthy dieting behaviour, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control at baseline, 8 and 16 w. The questionnaire had good reliability (Chronbach’s Alpha of 0.79)

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) version 16. Descriptive data are presented as mean and standard deviation, or standard error of mean, or percentage as appropriate. For continuous variables, differences within groups were tested by paired t-test. Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. An intention to treat (ITT) analysis was used in which missing data were replaced by the last observation carried forward. For the factor analysis, binary logistic regression was used to determine the association between demographic and health variables and versus BMI and TPB score post intervention. An odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were used to interpret the significance of an association, using a P<0.05 as the cut-off point for significance.

Results and Discussion

Initially, 112 participants were included in the study (as two groups with 56 participants each). The remaining 108 eligible participants met the investigators. A total of 52 participants received group behaviour counselling and 56 participants received individual behaviour therapy. No statistically significant difference of baseline characteristics between two study groups was found (Table 1). The average age of the participants was approximately 20 y. Most participants (65%) were female. About 90% had no underlying disease(s). More than 80% of them had previously attempted to control weight. Three-fourths (75%) used diet control. The average BMI at baseline was 27.55±3.04 kg/m2 for participants (male: 26.97±3.21; female: 27.74±2.99 kg/ m2) who received group counselling and 26.87±2.38 kg/m2 (male: 26.21±1.53; female: 27.24±2.68 kg/m2) for those received individual counselling. There were no significant differences among the two groups on any of baseline characteristics.

| Characteristics | Group counseling (n=52) | Individual counseling (n=56) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.77a | ||

| Female | 39 (66.1) | 36 (64.3) | |

| Age in years, mean±SD | 20.87±1.78 | 20.73±1.72 | 0.69b |

| Underlying disease | 0.87a | ||

| Non Underlying disease | 52 (92.9) | 52 (92.9) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (7.1) | 3 (5.4) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Attempted to control weight | 0.66a | ||

| Yes | 46 (82.1) | 51 (91.1) | |

| Method used for control weight | 0.72a | ||

| None | 9 (16.1) | 5 (8.9) | |

| Diet control | 42 (75.0) | 42 (75.0) | |

| Exercise | 3 (5.4) | 7 (12.6) | |

| Herbal use | 2 (3.5) | 2 (3.5) | |

| Height (m), mean±SD | 1.68±0.58 | 1.69±0.55 | 0.59b |

| Weight (kg), mean±SD | 78.23±6.83 | 76.94±6.25 | 0.31b |

| Waist Circumference (cm), mean±SD | 93.01±4.29 | 93.60±3.81 | 0.38b |

| BMI in kg/m2, mean±SD | 27.55±3.04 | 26.87±2.38 | 0.20b |

Statistical significance was tested by achi-square test and bindependent t-test

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes Of Participants

At baseline, there were no differences in weight, BMI and waist circumference between the two groups. As shown in Table 2, both groups showed improvement in all clinical outcomes at 16 w. Although, both types of counselling were able to decrease the mean weight, BMI and waist circumference significantly (P<0.05), the decrease in all clinical outcomes was greater when counselling individually. Similar reduction significantly in these outcomes in post-intervention compared to pre-intervention was observed for subgroup analysis. For female analysis, the average weight of individual counselling and group counselling was significantly different, 71.28±6.93 kg and 75.33±6.67 kg respectively (P=0.012). This phenomenon was not found among males.

| Outcomes | Mon 0 | Mon 6 | Δ | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | ||||

| Group counselling (n=56) | 78.23±6.83 | 74.07±6.85 | −4.2 | P<0.001b* |

| Individual counselling (n=56) | 76.94±6.26 | 71.71±6.49 | −5.2 | P<0.001b* |

| P-value | 0.312a | 0.039a* | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Group counselling (n=56) | 27.55±3.04 | 26.09±2.99 | −1.46 | P<0.001b* |

| Individual counselling (n=56) | 26.86±2.37 | 25.03±2.27 | −1.83 | P<0.001b* |

| P-value | 0.203a | 0.042a* | ||

| Waist circumference (cm.) | ||||

| Group counselling (n=56) | 93.01±2.95 | 91.71±2.97 | −1.30 | P<0.001b* |

| Individual counselling (n=56) | 93.57±3.81 | 91.67±3.99 | −1.90 | P<0.001b* |

| P-value | 0.377a | 0.062a |

Statistical significance was tested by aindependent t-test and bpaired t-test, *P≤0.05

Table 2: Clinical Outcomes

The average changes in the intermediate behavioural outcomes from baseline are illustrated in Table 3. No statistically significant differences between groups were found. At baseline, the low score was found in 6 domains of group counselling and five domains of individual counselling. At 6 mon, the average sum score of healthy dieting behaviour of the group counselling increased significantly from 7.65±3.95 to 9.17±3.33 (P=0.005). However, the individual counselling group showed a significant increase of average sum score in 2 domains (healthy dieting behaviour and subjective norm). The score of 3 domains and 5 domains at 6 mon were increased to higher levels for the group and individual counselling, respectively.

| Domain | Group counselling | D | P-valuea | Individual counselling | D | P-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre test | Post test | Pre test | Post test | |||||

| Healthy dieting behaviour | 7.65±3.95 | 9.17±3.33 | +1.52 | 0.005* | 8.54±4.17 | 10.32±2.96 | +1.78 | 0.004* |

| Intention to perform healthy dieting behaviour | 14.81±3.43 | 15.46±4.83 | +0.65 | 0.171 | 16.44±2.97 | 16.64±3.26 | +0.20 | 0.713 |

| Perceived behavioural control | 18.05±2.85 | 18.11±2.79 | +0.06 | 0.873 | 18.05±3.80 | 18.98±2.38 | +0.93 | 0.120 |

| Attitude towards healthy dieting behaviour | 16.15±3.67 | 16.81±3.62 | +0.66 | 0.162 | 17.23±2.82 | 17.63±2.68 | +0.40 | 0.270 |

| Subjective norm | 14.77±2.27 | 14.81±2.18 | +0.04 | 0.913 | 13.94±2.73 | 15.36±2.36 | +1.42 | P<0.001* |

| Control beliefs | 29.92±4.54 | 31.52±5.04 | +1.60 | 0.108 | 29.39±3.85 | 30.46±4.93 | +1.07 | 0.150 |

| Behavioural beliefs | 16.63±4.54 | 16.19±3.84 | -0.44 | 0.423 | 16.57±3.12 | 16.79±3.40 | +0.22 | 0.473 |

| Normative beliefs | 28.48±4.69 | 29.59±4.52 | +1.11 | 0.129 | 29.66±4.41 | 30.89±3.75 | +1.23 | 0.115 |

Note: *P≤0.05, aanalysed paired t-test, *P≤0.05

Table 3: Average Sum Score of Each Domain Obtain From TPB Questionnaire

The eating behaviour was measured by the TPB diet questionnaire. Three factors had influenced on intention to perform healthy dieting behaviour, attitude toward healthy dieting behaviour, behavioural beliefs and normative beliefs. Group counselling was over 4 times more likely to associate intention to perform healthy dieting behaviour score than individual counselling (OR=4.03, 95% CI: 1.71-9.51) but were less likely to associate with behavioural beliefs. Women were less likely to be associated with attitude toward healthy dieting behaviour score and normative beliefs score than men (OR=0.37, 95% CI=0.15-0.93 and 0.25, 95% CI=0.09-0.57, respectively). People with attempted to weight control were favourable to intention to perform healthy dieting behaviour score (OR=0.17, 95% CI=0.03-0.91). Underlying disease and BMI status were not significantly associated with eating behaviour (Table 4).

| Variables | Healthy dieting | Intention | Perceived | Attitude | Subjective norm | Control beliefs | Behavioral beliefs | Normative beliefs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95%CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Counselling | |||||||||||||||||

| Individual | 1 | 0.12-0.67 | 1 | 1.71-9.51 | 1 | 0.87-7.52 | 1 | 0.39-2.37 | 1 | 0.38-1.97 | 1 | 0.34-3.19 | 1 | 0.04-0.62 | 1 | 0.74-3.83 | |

| Group | 0.96 | 4.03* | 2.56 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 1.04 | 0.16* | 1.69 | |||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||

| Male | 1 | 0.07-8.25 | 1 | 0.32-1.98 | 1 | 0.12-1.06 | 1 | 0.15-0.93 | 1 | 0.54-3.15 | 1 | 0.56-5.90 | 1 | 0.06-1.43 | 1 | 0.09-0.57 | |

| Female | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.36 | 0.37* | 1.29 | 1.82 | 0.28 | 0.23* | |||||||||

| Underlying disease | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1 | 0.16-2.63 | 1 | 0.39-9.95 | 1 | 0.09-7.52 | 1 | 0.05-3.91 | 1 | 0.10-1.92 | 1 | 0.07-2.24 | 1 | 0.17-16.97 | 1 | 0.36-7.26 | |

| No | 0.20 | 1.96 | 0.83 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 1.73 | 1.62 | |||||||||

| Attempted to weight control | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1 | 0.29-3.37 | 1 | 0.03-0.91 | 1 | 0.10-2.07 | 1 | 0.19-3.58 | 1 | 0.18-3.01 | 1 | 0.08-5.68 | 1 | 0.44-10.34 | 1 | 0.14-1.98 | |

| No | 0.48 | 0.17* | 0.46 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 2.13 | 0.53 | |||||||||

| BMI status | |||||||||||||||||

| Overweight | 1 | 0.37-39.35 | 1 | 0.19-1.08 | 1 | 0.22-1.78 | 1 | 0.25-1.53 | 1 | 0.41-2.12 | 1 | 0.20-1.98 | 1 | 0.67-7.08 | 1 | 0.56-2.91 | |

| Obesity | 3.81 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.93 | 0.64 | 2.18 | 0.88 | |||||||||

*P≤0.05

Table 4: Associations between Clinical Outcomes, Participants’ Factors and Eating Behavior (TPB Score)

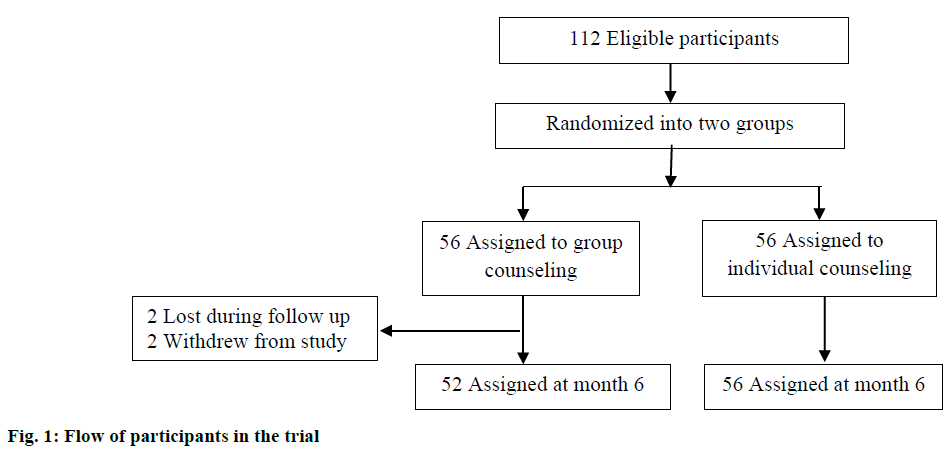

This randomized study was conducted to compare the outcomes of two types of counselling; group counselling and individual (one-on-one) counselling at a community pharmacy. At the beginning of the study, 112 participants were enrolled. Four participants in the control group withdrew from the study as shown in Figure 1. The majority of participants were females (~60%), in agreement with previous studies which reported higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in female university students [19]. An effect of individual counselling was superior to group counselling for weight loss and BMI. However, both interventions produced significantly improved clinical outcome at the end of trial.

Approximately 6% weight loss at 6 mon was impressive considering that most previous studies have shown 5-10% weight loss along with well documented positive effects on biomarkers for cardiovascular disease [20]. Effect on weight loss (4.20% in group counselling and 5.20% in individual counselling) was consisted with the other studies using the intervention based on counselling. Both interventions lost more weight than pre-intervention. However, individual counselling significantly decreased weight and BMI greater than group counselling. Our findings are in disagreement with previous studies that have compared group counselling and individual counselling in the obesity and overweight population [21]. One study in Thailand performed group counselling intervention compared to individual counselling and reported that both types of counselling during a 1 y period did not significantly improve clinical outcomes [14]. On the other hand, Renjilian et al. [16] reported that group counselling produced significantly greater reductions in weight and BMI than individual counselling. These results consisted of one RCT in Thailand conducted by Smanchart et al. This study used an individual advice which found that individual weight-loss counselling in university students is not effective in 6 mon [17]. Comparing to ours, the Samanchart study [17] had the weight loss attempt and subjective norm score at the baseline lower than the control group significantly. This may cause failure to achieve weight loss. In the subgroup analysis, women maintain significant weight loss in 6 mon. The possible explanation was the differences in fat metabolism and storage between male and female subjects [22].

Our study showed an improvement in average TPB scores. The group counselling can achieve changing healthy dieting behaviour. Individual counselling can successfully change healthy diet and subjective norm. Our study disagrees with a previous study in university students which found that individual counselling can increase TPB domain at 6 mon [17]. However, our findings agree with several other studies which found that university students have higher scores of eating behaviour especially; attitude and perceived behavioural control [23]. The possible cause of not seeing the TPB scores change significantly from baseline may be due to personality traits which are hard to change [14]. Our study has investigated the factors associated with TPB score including type of counselling, gender and attempt at weight control. Group counselling was found to be associated with intension score. This agrees with a previous study [24]. The possible reason was that group counselling may create an environment that helps people accept their disease and facilitates behaviour changes. Moreover, therapeutic factors like group learning and group optimism probably help create this positive environment [25]. Our study found that males are associated with good attitude of eating behaviour. Other studies have found no relationship between gender and attitudes toward obesity [26]. From this study it is shown that gender differences may require the need for separate programs or at least special considerations for male and female. Attempted at weight control is significantly associated with intention score. This finding agrees with previous studies that reported attempts to lose weight interpreted as intention to lose weight [27].

No adverse effects were found during the study. This study did not exclude the under controlled patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia which are highly prevalent in the overweight and obese population. Generally, these patients received a recommendation from their physician to control their diet and weight to improve disease management and decrease health risks.

Several limitations of this study are noted which include the small sample size, and a short duration (6 mon). We have evaluated clinical outcomes only among young adults, who may have more intention to lose weight. This possibly led to positive impact of the program. Thus, our results may not be generalized to the other age groups.

In conclusion, it is clear that both group and individual counselling are effective in reducing weight, BMI and waist circumference of young adults. Since, the effect of both groups was not significantly different; we suggest using group counselling due to less cost and time. However, further study over a longer period of time with a larger number of subjects is needed to verify these results and enhance generalizability to other age groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Faculty of Pharmacy, Mahasarakham University for research facilities. In addition, appreciation is expressed to participants, and pharmacy students who assisted in the investigation. Finally, thanks to Prof. Gary H. Smith, University of Arizona College of Pharmacy, Tucson, Arizona, USA, for editorial assistance.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Field A, Coakley E, Must A. Impact of overweight on the risk of developing common chronic diseases during a 10-year period. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1581-6.

- Fontaine K, Redden D, Wang C, Westfall A, Allison D. Years of Life Lost Due to Obesity. JAMA2003;289:187-93.

- World Health Organisation. Obesity and overweight. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2013.

- Aekplakorn W, Mo-Suwan L. Prevalence of obesity in Thailand. Obes Rev 2009;10:589-92.

- Fila SA, Smith C. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to healthy eating behaviors in urban Native American youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2006;3:11.

- Kantachuvessiri A. Obesity in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai 2005;88:554-62.

- Roongpisuthipong C, Panpakdee O, Boontawee A, Kulapongse W. Behavior modification in the treatment of obesity. J Med Assoc Thai 1993;76:617-22.

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol Health 2011;26:1113-27.

- Conner M, Norman P, Bell R. The theory of planned behavior and healthy eating. Health Psychol 2002;21:194-201.

- Kim K, Reicks M, Sjoberg S. Applying the theory of planned behavior to predict dairy product consumption by older adults. J Nutr Educ Behav 2003;35:294-301.

- Verbeke W, Vackier I. Individual determinants of fish consumption: application of the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite 2005;44:67-82.

- Hackman CL, Knowlden AP. Theory of reasoned action and theory of planned behavior-based dietary interventions in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Adolesc Health Med Ther2014;5:101-14.

- Waleekhachonloet O, Limwattananon C, Limwattananon S. Explaining diet control in overweighing and obese women living in rural using theory of planned behavior: structural equation modeling. Qual Life Res 2005;14:2034.

- Waleekhachonloet O, Limwattananon C, Limwattananon S, Gross CR. Group behavior therapy versus individual behavior therapy for healthy dieting and weight control management in overweight and obese women living in rural community. Obes Res Clin Pract 2007;1:223-32.

- Phimarn W, Pianchana P, Limpikanchakovit P, Suranart K, Supapanichsakul S, Narkgoen A, et al. Thai community pharmacist involvement in weight management in primary care to improve patient’s outcomes. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35:1208-17.

- Renjilian DA, Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Anton SD. Individual versus group therapy for obesity: effects of matching participants to their treatment preferences. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001;69:717-21.

- Samanchat P, Waleekhachonloet O, Towanna B. Effect of the Weight Control Program Focusing on the Modification of Eating Behavior in the Overweight or Obese University Students. TJPP 2010;2:35-45.

- Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, Makris AP, Rosenbaum DL, Brill C. Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:147-57.

- Peltzer K, Pengpid S, Samuels TA, Özcan NK, Mantilla C, Rahamefy OH. Prevalence of Overweight/Obesity and Its Associated Factors among University Students from 22 Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:7425-41.

- Blackburn G. Effect of degree of weight loss on health benefits. Obes Res 1995;3:211s-6s.

- Kalavainen MP, Korppi MO, Nuutinen OM. Clinical efficacy of group-based treatment for childhood obesity compared with routinely given individual counselling. Int J Obes 2007;31:1500-8.

- Blaak E. Gender differences in fat metabolism. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2001;4:499-502.

- Nejad L, Wertheim E, Greenwood K. Predicting dieting behaviour by using, modifying, and extending the theory of planned behaviour. J Appl Soc Psychol 2004;34:2099-31.

- Paranjape A. Intentions, attitudes, and perceived behaviour control towards healthy nutrition behaviours of individuals participating in a group counselling program versus those receiving individual counselling. Kent, OH, USA: MSc Thesis, Kent State University; 2011.

- Cooper HC, Booth K, Gill G. Patients' perspectives on diabetes health care education. Health Edu Res 2003;18:191-206.

- Garner CM, Nicol GT. Comparison of male and female nurses' attitudes toward obesity. Percept Mot Skills1998;86:1442.

- Sørensen TIA, Rissanen A, Korkeila M, Kaprio J. Intention to Lose Weight, Weight Changes, and 18-y Mortality in Overweight Individuals without Co-Morbidities. PLoS Med 2005;2:e171.