- *Corresponding Author:

- T. A. Aburjai

Faculty of Pharmacy, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid-Jordan

E-mail: aburjai@ju.edu.jo

W. Alshaer

Cell Therapy Center, The University of Jordan, Amman-Jordan

| Date of Submission | 11 July 2019 |

| Date of Revision | 07 October 2019 |

| Date of Acceptance | 24 December 2019 |

| Indian J Pharm Sci 2020;82(1):179-184 |

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms

Abstract

In the current study, the compositions of the essential oil obtained from leaves of Ocimum basilicum ‘Cinnamon’ grown in Jordan in a greenhouse was analysed. The antitumor activity of the essential oil was examined against three different cancer cell lines including MDA-MB-231, MCF7 and U-87 MG. The hydrodistillation method was used to extract the essential oil from Ocimum basilicum and the chemical components were analyzed and identified using gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy. The dry weight yield of essential oil was 0.50 % (w/w). Thirty-one components representing 97.80 % of the essential oil were identified. The main chemical components revealed the presence of linalool, eugenol, eucalyptol, hinesol, trans-α-bergamotene and γ-cadinene as the major constituents. In conclusion, the essential oil extracted from greenhouse cultivated Ocimum basilicum European chemotype showed potent antitumor activity.

Keywords

Basil, Ocimum basilicum, essential oils, greenhouse cultivation, antitumor, cancer

Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) is a culinary herb of the family Lamiaceae and considered as one of the most aromatic plants grow widely at different places around the world, especially in Asia, North America, and Europe[1,2]. Basil is used for many applications in the pharmaceutical and food industry[3]. Traditionally, sweet basil has been used as a medicinal plant in the treatment of kidney malfunction, worms, cough, diarrhea and headache[1,4-8]. Moreover, basil contains a group of phenolic compounds that impart a good antioxidant effect[5,9-11]. O. basilicum is a popular culinary herb and a source of essential oils extracted from leaves and flowering tops that are used in flavoring foods, dental and oral products and fragrances[4].

Essential oil of basil primarily consists of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes and phenylpropanoids with oxygenated derivatives[1,3,12,13]. There are important differences among basil species including the variation in the chemical compositions and the essential oil content and components. In addition to the species, such variation may be linked to the growing and cultivation environment that varies among different locations[1,14]. There are two main types of basil oil commonly used in the market, the reunion type which is mostly composed estragole (80 %) and (ii) the European type usually obtained from France, Italy, Egypt, and South Africa, which is mostly composed of linalool (35-50 %) and estragole (15-25 %)[15].

Cancer is a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by the uncontrolled growth of cells that escape from body defenses and many times from the conventional antitumor drugs. Cancer is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In 2018, 18.1 million new cancer cases were diagnosed and 9.6 million cancer-related deaths were reported[16,17]. The development of new therapeutics and therapeutic systems is a continuous battle for successful and effective cancer treatment. Tumor cells are heterogeneous and can develop intrinsic or acquired multidrug resistance mechanisms including increased drug efflux, drug inactivation, drug target alteration, increased DNA damage repair, epigenetics, cell death inhibition and epithelial-mesenchymal transition[18,19]. Plants are considered a rich source of natural compounds that can be used for the discovery of anticancer agents. Around 50 % of conventional anticancer chemotherapeutics are originated from plants. One important example is paclitaxel which is widely used for the treatment of different types of cancers, including breast, ovarian and pancreatic cancer[20-22]. Essential oils are aromatic secondary metabolites of plants that possess wide range bioactivities with pharmacological interests including anticancer activity[23,24]. Consequently, adding more therapeutic options for cancer prevention.

It appears based on the literature search, no studies were reported in which the composition of the essential oil of O. basilicum grown in Jordan was investigated. Therefore, this study was taken up to carry out a detailed chemical investigation of the essential oil composition of the chemotypes of O. basilicum grown in Jordan. Moreover, this study aimed to investigate the anticancer activity of essential oil of O. basilicum grown in a greenhouse.

Seeds of O. basilicum ‘cinnamon’ were collected from a mother plant grown in the botanical garden of Faculty of Agriculture, The University of Jordan (UJ)-Amman, seeded and transplanted for cultivation under controlled greenhouse conditions; 25° and 40-60 % relative humidity with conventional cultivation practices of irrigation and fertilization (20-20-20-TE). Basil leaves were collected when the height of the plant reached 20-25 cm. Plant material was taxonomically identified by direct comparison with an authenticated sample at the herbarium of the Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, the University of Jordan. A voucher specimen of plant material was deposited at the School of Pharmacy, JU (GH-B-18, for greenhouse). N-hexane (GC grade) was purchased from Tedia (USA), A hydrocarbon mixture of n-alkanes (C8-C20) was purchased from Fluka (Switzerland).

Plant material (500 g) was collected as mentioned above and dried at room temperature in a shaded and ventilated area. Dried plant material (100 g) was hydrodistilled for 3 h using the Clevenger apparatus (JSGW, India). The obtained essential oil was separated, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate (Analar, England) and stored in a sealed vial in the refrigerator. The yield of oil was calculated as percent weight by weight (w/w %) of the dry plant material.

A 5 μl aliquot of oil samples diluted with 1 ml of GCgrade n-hexane and then 1 μl samples of the diluted oil were injected into the GC-MS systems for analysis. From the diluted oil sample prepared above, 1 μl aliquot was injected using an automated injector into the GCMS system for analysis using a variant chrompack CP- 3800 GC/MS/MS-200 (Satum, Netherlands) equipped with split-splitless injector and DB-5 capillary column (5 % diphenyl 95 % dimethyl polysiloxane, 30 m×0.25 mm ID, 0.25 μm film thickness). The injector temperature was set at 250° with a split ratio of 1:30. A linear temperature program was used to separate the different oil components. The column temperature was held constant at 60° for 1 min. The temperature was then increased to 250°, at a rate of 3°/min and then was held constant at 250° for 2 min, with a total runtime of about 66 min. The flow rate of the carrier gas (helium) was 1 ml/min. Each sample was analyzed twice. The mass detector was set to scan ions between 40-400 m/z using full scan mode and electron impact (El, 70 eV). A hydrocarbon mixture of n-alkanes (C8-C20) was analyzed separately by GC-MS using the same column (DB-5) and under the same chromatographic conditions. Linear retention index (Arithmetic-Kovats index) was calculated for each component (each peak) separated by GC-MS using the value of its retention time and the retention times of the reference n-alkanes applying Van Den Dool Eqn.[25]. The constituents of the essential oils were identified using their recorded mass spectra and the built-in computerized matching with WILEY, NIST and ADAMS libraries, and by comparing their calculated arithmetic indices with reported values in the literature[26]. Identification of linalool, eugenol, and eucalyptol was further confirmed by co-chromatography with authentic standards (Sigma-Aldrich) under the same chromatographic conditions mentioned above.

GC-FID analysis was also carried out to obtain qualitative complementary results to those obtained by GC-MS as well as to obtain quantitative measures of the identified compounds. GC-FID was carried out on a ThermoQuest gas chromatograph coupled to an FID detector equipped with a split-splitless injector (split ratio 1:30) and HP-5 capillary column (Crosslinked 5 % PH ME Silicone, 30 m×0.32 mm×0.25 μm film thickness). One microlitre aliquots were autoinjected into the GC-FID system and analyzed using the same linear temperature program applied in the GCMS analysis above. The carrier gas was nitrogen (N2 99.99 %) and the flow rate was 1 ml/min. Each sample was analyzed triplicate. Essential oil constituents were identified by calculating the linear retention index of each constituent relative to (C8-C20) n-alkanes mixture (which was analyzed separately by GC-FID using the same column) and applying Van Den Dool Eqn.[25]. To identify the constituents, the calculated arithmetic indices were then compared with reported values in the literature[26]. Constituents quantification was achieved by dividing the peak area of each constituent by the total peak area of all oil constituents and multiplying the result by 100.

U-87 MG (glioblastoma cell line), MCF7 (ER+ breast cancer) and MDA-MB-231 (triple negative breast cancer cell line), were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC®; USA). U-87 MG was cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM, ATCC®, USA), containing 1 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and 10 % fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA). MCF7 was maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (RPMI; Euroclone, UK) supplemented with 1 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and 10 % fetal bovine serum. MDA-MB-231 was cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM, Euroclone, UK) supplemented with 1 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and 10 % fetal bovine serum. Cells were grown at 37° in 5 % CO2 atmosphere.

U-87 MG, MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 were seeded in 96-well plates at 7000 cells/well in 0.1 ml in complete EMEM, RPMI and MEM consequently. After 24 h, cells were treated and incubated with different concentrations of basil extract for 72 h at 37°. Afterward, the old media was aspirated and 100 μl of fresh medium and 15 μl of MTT reagent was added to each well and incubated for 4 h to allow the formation of formazan crystals. After removing all media from the wells, 50 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well and mixed carefully. The absorbance values were measured using a microplate reader (GloMax®-Multi+ Detection System) at 570 nm to determine relative viabilities. Finally, data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 6.

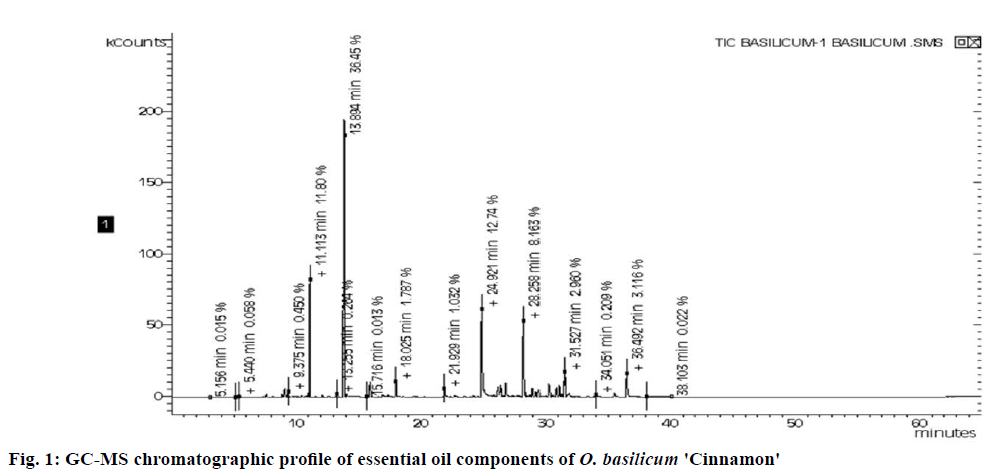

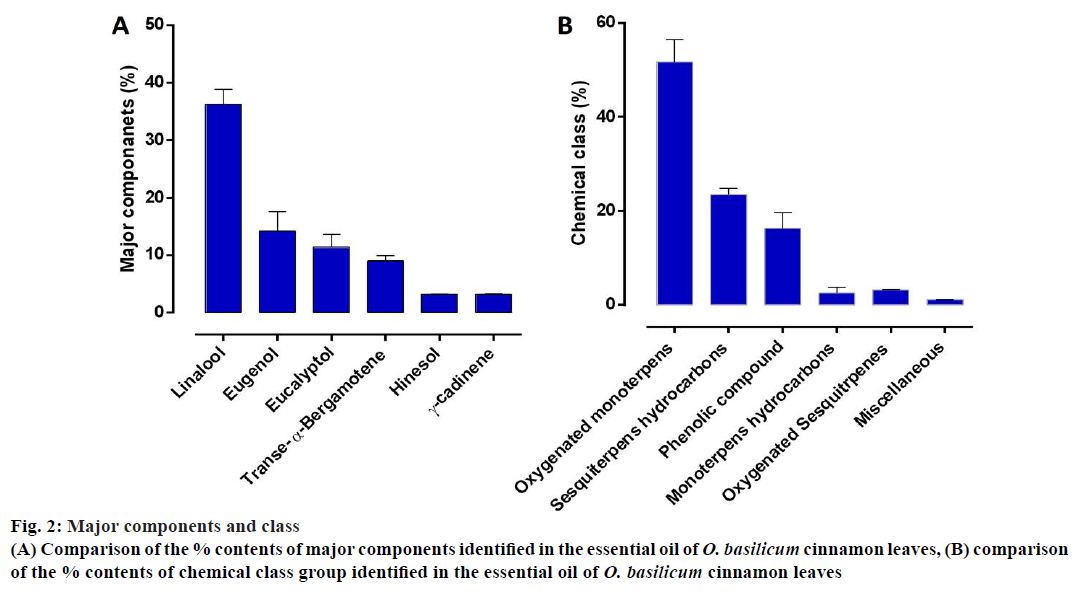

The results obtained revealed the presence of 31 components of the essential oil of O. basilicum based on GC-MS analysis (Figure 1). The identified compounds are listed in Table 1 in elution order from the DB-5 column, along with the percent composition of each component, its KI and class. The major constituents of the essential oil of O. basilicum were linalool (36 ±2.6 %), eugenol (14.2±3.4 %), eucalyptol (11.4±2.2), trans-α-bergamotene (9.0±0.9 %), hinesol (3.2±0.1 %), and γ-cadinene (3.1±0.1 %) summarized in figure 2A.

| Compound name | Formula | Mol weight (g/mol) | KI* cal. | KI** lit. | % content GH (Avg±SD) 5 µl oil/1 ml hexane |

Chemical class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Pinene | C10H16 | 136.24 | 934 | 932 | 0.28±0.02 | Monoterpene hydrocarbon |

| Sabinene | C10H16 | 136.23 | 973 | 969 | 0.31±0.05 | Monoterpene hydrocarbon |

| β-Pinene | C10H16 | 136.24 | 980 | 974 | 0.88±0.21 | Monoterpene hydrocarbon |

| Myrcene | C10H16 | 136.24 | 988 | 988 | 0.44±0.13 | Monoterpene hydrocarbon |

| Limonene | C10H16 | 136.24 | 1030 | 1024 | 0.30±0.09 | Monoterpene hydrocarbon |

| Eucalyptol (1,8-cineol) | C10H18O | 154.25 | 1034 | 1026 | 11.36±2.23 | Oxygenated monoterpene |

| Terpinolene | C10H16 | 136.24 | 1087 | 1086 | 0.26±0.05 | Monoterpene hydrocarbon |

| Linalool | C10H18O | 154.25 | 1101 | 1095 | 36.26±2.58 | Oxygenated monoterpene |

| Trans-sabinenehydrate | C10H18O | 154.25 | 1105 | 1098 | 0.47± 0.02 | Monoterpene hydrocarbon |

| Camphor | C10H16O | 152.24 | 1150 | 1141 | 1.61±0.09 | Oxygenated monoterpene |

| δ-Terpineol | C10H18O | 154.25 | 1172 | 1162 | 0.26±0.02 | Oxygenated monoterpene |

| Terpinen-4-ol | C10H18O | 154.25 | 1182 | 1174 | 0.24±0.00 | Oxygenated monoterpene |

| α-Terpineol | C10H18O | 154.25 | 1197 | 1186 | 1.91±0.07 | Oxygenated monoterpene |

| Bornyl acetate | C12H20O2 | 196.29 | 1286 | 1287 | 1.11±0.02 | Miscellaneous |

| Eugenol | C10H12O2 | 164.20 | 1355 | 1356 | 14.2±3.36 | phenolic compound |

| β-Elemene | C15H24 | 204.36 | 1391 | 1389 | 2.78±0.02 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| Methyl eugenol | C11H14O2 | 178.23 | 1400 | 1403 | 2.1±0.00 | Phenolic compound |

| Trans-α-bergamotene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 1434 | 1432 | 9.00±0.86 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| α-Guaiene | C15H24 | 204.36 | 1438 | 1437 | 0.41±0.15 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| Trans-β-farnesene | C15H24 | 204.36 | 1452 | 1454 | 1.00±0.08 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| α-Humulene | C15H24 | 204.36 | 1458 | 1452 | 0.59±0.02 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| Cis-murrola-4(14),5-diene | C15H24 | 204.36 | 1464 | 1465 | 0.86±0.04 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| Germacrene D | C15H24 | 204.36 | 1483 | 1484 | 2.01±0.16 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| Cis-β-guaiene | C15H24 | 204.36 | 1491 | 1492 | 0.29±0.01 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| Valencene | C15H24 | 204.36 | 1498 | 1496 | 0.99±0.04 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| Trans-β-guaiene | C15H24 | 204.36 | 1504 | 1502 | 1.31±0.08 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| Cis-α-bisabolene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 1509 | 1506 | 0.37±0.05 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| γ-cadinene | C15H24 | 204.36 | 1515 | 1513 | 3.2±0.11 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| Trans-calamenene | C15H22 | 202.34 | 1522 | 1521 | 0.28±0.00 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| β-Sesquiphellandrene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 1524 | 1521 | 0.60±0.19 | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon |

| Hinesol | C15H26O | 222.37 | 1645 | 1640 | 3.17±0.07 | Oxygenated sesquiterpene |

KI* cal. linear (arithmetic) retention index calculated on a DB-5 equivalent column; KI** lit. Reference retention index value from literature; ND is not detected

Table 1: Composition of the essential oil of O. basilicum

The chemical components of sweet basil have been described in several reports. For example, Kruger et al. reported the major components of 270 sweet basil accessions[27]. The major constituents were found to be linalool, methyl chavicol, citral, 1,8-cineole, camphor, thymol, methyl cinnamate, eugenol, methyl eugenol, methyl isoeugenol and elemicin[27]. Moreover, Marotti et al. have reported the major oil constituents of different basil chemotypes such as in the Italian basil type linalool and methyl chavicol, in the tropical basil chemotype, methyl cinnamate and in the basil chemotype grown in North Africa, Russia, Eastern Europe and parts of Asia was eugenol[28].

The major components of the essential oil can be classified into 5 major classes including oxygenated monoterpenes (51.7±4.8), sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (23±1.4), phenolic compounds (16.3±3.3), oxygenated sesquiterpenes (2.6±1.1) and monoterpene hydrocarbons (3.2±0.1). These major components represent 97.1 % of the essential oil (Figure 2B).

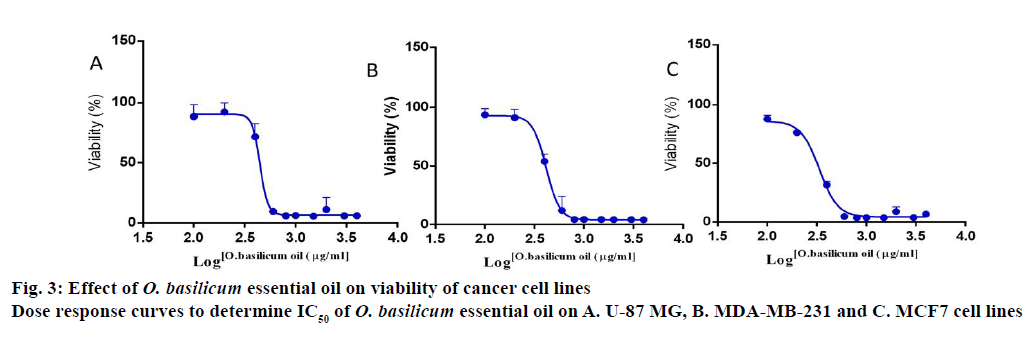

After analyzing the major components and chemical classes of the O. basilicum essential oil, an attempt was made to investigate the anticancer effect against known common and invasive cancers. For this purpose, 3 cancer cell lines were chosen for representing two types of cancers, including a triple negative breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231), ER+ breast cancer (MCF7), and the glioblastoma (U-87 MG). The cells were treated with different concentrations of essential oil for 72 h followed by the detection of viable cells using MTT assay. The inhibitory concentrations 50 (IC50) were calculated based on the percent remaining viable cells of 3 independent experiments. The IC50 values were 432.3±32.2 μg/ml on MDA-MB-231, 320.4±23.2 μg/ml on MCF7 and 431.2±15.3 μg/ml on U-87 MG as shown in figure 3. These results agree with previously reported results. Linalool, eugenol and eucalyptol are the major components of O. basilicum essential oil, which have been shown to exhibit anticancer effect against different types of cancers such as leukemia, lymphoma, breast, colorectal, bone sarcoma, hepatic, gastric, lung and melanoma[14,29-31]. Interestingly, linalool was reported to potentiate doxorubicin on both MCF7 breast cancer and the doxorubicin-resistant MCF7/Adr cells through inducing apoptosis[32]. Different mechanisms have been described for such anticancer effects, including the induction of DNA repair, apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, detoxification and antioxidant enzymes[29-31].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the essential oil composition of O. basilicum grown in Jordan and its chemotype. The main essential oil components of O. basilicum were linalool/eugenol, suggested the linalool chemotype essential oil of O. basilicum European chemotype. In the literature, there is a low amount of data describing the anticancer effect of O. basilicum essential oil on triple-negative breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231), ER+ breast cancer (MCF7), and the glioblastoma (U-87 MG). The findings of this study revealed the promising anticancer effect of O. basilicum essential oil cultivated in Jordan.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment:

The authors are grateful to the Deanship of Scientific research, University of Jordan, Amman – Jordan for supporting this work (Fund No. 2086). Authors thank Prof, Dr. Dawoud Al-Issawi, Plant taxonomist, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, JU for authenticating the plant material.

References

- Pripdeevech P, Chumpolsri W, Suttiarporn P, Wongpornchai S. The chemical composition and antioxidant activities of basil from Thailand using retention indices and comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography. J Serb Chem Soc 2010;75(11):1503-13.

- Sajjadi SE. Analysis of the essential oils of two cultivated basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) from Iran. DARU J Pharm Sci 2006;14(3):128-30.

- Svecova E, Neugebauerova J. A study of 34 cultivars of basil (Ocimum L.) and their morphological, economic and biochemical characteristics, using standardized descriptors. Acta Univ Sapientiae Alimentaria 2010;3:118-35.

- Joshi RK. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Ocimum basilicum L.(sweet basil) from Western Ghats of North West Karnataka, India. Anc Sci Life 2014;33(3):151.

- Politeo O, Jukic M, Milos M. Chemical composition and antioxidant capacity of free volatile aglycones from basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) compared with its essential oil. Food Chem 2007;101(1):379-85.

- Özcan M, Arslan D, Ünver A. Effect of drying methods on the mineral content of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.). J Food Eng 2005;69(3):375-9.

- Grayer RJ, Vieira RF, Price AM, Kite GC, Simon JE, Paton AJ, et al. Characterization of cultivars within species of Ocimum by exudate flavonoid profiles. Biochem Syst Ecol 2004;32(10):901-913.

- Baratta MT, Dorman HJD, Dean SG, Figueiredo C, Barroso JG, Ruberto G. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of some commercial essential oils. Flavour Fragrance J 1998;13(4):235-44.

- Hussain AI, Anwar F, Hussain Sherazi ST, Przybylski R. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of basil (Ocimum basilicum) essential oils depends on seasonal variations. Food Chem 2008;108(3):986-95.

- Telci I, Bayram E, Yilmaz G, Avci B. Variability in essential oil composition of Turkish basils (Ocimum basilicum L.). Biochem Systematics Ecol 2006;34(6):489-97.

- Lee SJ, Umano K, Shibamoto T, Lee KG. Identification of volatile components in basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and thyme leaves (Thymus vulgaris L.) and their antioxidant properties. Food Chem 2005;91(1):131-7.

- Lucchesi ME, Chemat F, Smadja J. Solvent-free microwave extraction of essential oil from aromatic herbs: comparison with conventional hydro-distillation. J Chromatogr A 2004;1043(2):323-7.

- Diaz-Maroto M, Pérez-Coello MS, Cabezudo M. Headspace solid-phase microextraction analysis of volatile components of spices. Chromatographia 2002;55(11-12):723-8.

- Dhifi W, Bellili S, Jazi S, Bahloul N, Mnif W. Essential oils’ chemical characterization and investigation of some biological activities: a critical review. Medicines 2016;3(4):25.

- Sakkas H, Papadopoulou C. Antimicrobial activity of basil, oregano, and thyme essential oils. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2017;27(3):429-38.

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68(6):394-424.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68(1):7-30.

- Wind N, Holen I. Multidrug resistance in breast cancer: from in vitro models to clinical studies. Int J Breast Cancer 2011;2011:967419.

- Gottesman MM. Mechanisms of cancer drug resistance. Annu Rev Med 2002;53(1):615-27.

- Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, Schneeweiss A, Barrios CH, Iwata H, et al. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379(22):2108-21.

- Yang H, Mao W, Rodriguez-Aguayo C, Mangala LS, Artholomeusz G, Iles LR, et al. Paclitaxel sensitivity of ovarian cancer can be enhanced by knocking down pairs of kinases that regulate MAP4 phosphorylation and microtubule stability. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24(20):5072-84.

- Rivera F, Benavides M, Gallego J, Guillen-Ponce C, Lopez-Martin J, Küng M. Tumor treating fields in combination with gemcitabine or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel in pancreatic cancer: Results of the PANOVA phase 2 study. Pancreatology 2019;19(1):64-72.

- Blowman K, Magalhães M, Lemos MFL, Cabral C, Pires IM. Anticancer properties of essential oils and other natural products. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2018;2018:3149362.

- Seca AM, Pinto DC. Plant secondary metabolites as anticancer agents: successes in clinical trials and therapeutic application. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19(1):263.

- van den Dool H, Kratz PD. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. J Chromatogr A 1963;11:463-71.

- Adams RP, Sparkman OD. Review of Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2007;18:803-6.

- Kruger HS, Wetzel B, Zeiger B. The chemical variability of Ocimum species. J Herbs Spices Med Plants 2002;9(4):335-44.

- Marotti M, Piccaglia R, Giovanelli E. Differences in essential oil composition of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Italian cultivars related to morphological characteristics. J Agric Food Chem 1996;44(12):3926-9.

- Andrade MA, Braga MA, Cesar PHS, Trento MVC, Espósito MA, Silva LF, et al. Anticancer Properties of Essential Oils: an overview. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2018;18(10):957-966.

- Bhalla Y, Gupta VK, Jaitak V. Anticancer activity of essential oils: a review. J Sci Food Agric 201393(15):3643-53.

- Gautam N, Mantha AK, Mittal S. Essential oils and their constituents as anticancer agents: a mechanistic view. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:154106.

- Ravizza R, Gariboldi MB, Molteni R, Monti E. Linalool, a plant-derived monoterpene alcohol, reverses doxorubicin resistance in human breast adenocarcinoma cells. Oncol Rep 2008;20(3):625-30.